Partner Article

Social media ‘road rage’ syndrome identified

Despite a national television and poster campaign recently launching to promote the world’s largest social media platform as the ideal place to make meaningful connections, new research today reveals that on these networks we’re actually less empathetic and tolerant of others, more likely to become easily enraged, and quicker to say things in anger that we later regret.

Through a new study, experts today have identified a pervasive new version of ‘road rage’ unique to the Information Superhighway, and particularly rife in users of popular social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter.

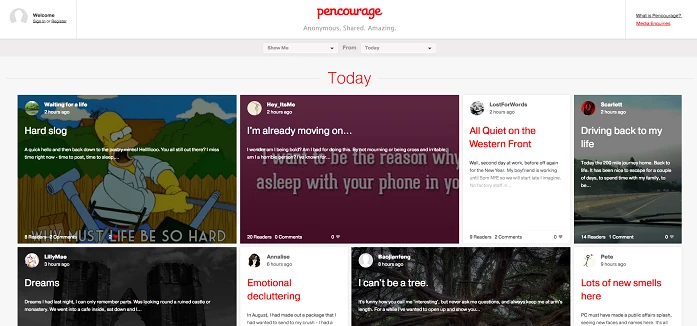

New statistics compiled by independent survey company OnePoll and commissioned by anonymous online journal repository Pencourage (www.pencourage.com); known as the ‘anti-Facebook’ for its tradition of no holds barred truth-telling; have uncovered a new condition similar to the reckless, aggressive and vengeful behaviour traditionally associated with vehicle drivers, who elsewhere would be unlikely to demonstrate any such hostile or belligerent personality traits.

When polling 1,000 social network users around Britain, well over four out of five (84%) admitted they become more easily exasperated, annoyed and enraged at others when online than they ever would in person; and well over a third (35%) have posted a reply, comment, status or Tweet in anger which they’ve later regretted.

Nearly half (47%) say they find themselves less tolerant of others’ problems and circumstances than in a face-to-face situation; a phenomenon a lot more rife in the 18-24 year old group, with 52% admitting that they are less accepting and patient online of other people’s issues or situations.

According to Pencourage founder Peter Clayton, whose anonymous site already hosts close to 70,000 personal diaries and enjoys a uniquely troll-free, non-judgmental environment where ‘txtspk’ is banned and positive feedback rewarded;

“The concept of ‘Road Rage’ on the Superhighway hardly comes as a shock to us. What is surprising however, is that most social networks are putting young people in the driver’s seat – then abdicating any responsibility for tough policing. Social media can be like a high octane drug that fuels less than stellar behaviour, we see it every day. On the one hand you have the invulnerability of no direct human contact, the equivalent of flipping the finger to another driver, on the other, being on the receiving end of this new social norm of aggressive behaviour. It polarises how the average person normally reacts, exaggerating the way people would interact in real life.”

Dr. Richard Sherry is a Clinical Psychologist, a Psychoanalytic Psychotherapist, and founding member of the Society for Neuropsychoanalysis. His Institute for Applied Social Innovation (IASI – www.instituteforappliedsocialinnovation.org) is conducting its own ground-breaking study into the psychological impact of each of the most popular platforms including Britain’s only social network, diary site Pencourage.

Dr. Sherry is unsurprised at the findings and says they already correlate with the preliminary results of his own independent research. He feels there needs to be a health warning on many of the most popular sites, and that users should take precautions before engaging online – just like we would before operating heavy machinery or getting behind the wheel of a car. He has christened the phenomenon social media or online ‘road rage’ and says;

“The mission of the world’s biggest social media site may well be to make us ‘more open and connected’, yet somehow this is not working in the way it is supposed to. This research shows that, if anything, the online space seems to be robbing us of some of the most fundamental aspects of our humanity.When using these sites, people are less likely to feel empathy, patience or compassion towards others; they are significantly quicker to judge and more dangerously reactive in their anger than they ever would be in a real life situation.

“Traditional road rage involves a strong sense of entitlement, which trigger a heightened sense of anger or rage at feeling wronged, for example, if someone cuts one off. The self-centred sense of power – the street is somehow an extension of ‘our space’, and we are safely protected by the anonymity of our vehicle – makes it seem our ‘right’ to act out. And just like on the Internet, we don’t see up close the faces or reactions of other drivers. This is why we can become so emotionally reactive when behind the wheel, for example making a rude gesture or swearing, when we would rarely do this face-to-face. These aggressive outbursts; whether resulting from being cut off at a junction or being confronted with an online status that somehow seems to directly rile us; tend to be grossly out of proportion with the situation – we overpersonalise a perceived slight, react impulsively and later might feel remorse or embarrassment.

“It’s a dangerous combination when this happens to someone operating a vehicle – clearly there is risk of physical injury if not worse. But the psychological damage we can cause to ourselves and others must undoubtedly also be taken into account when interacting via social media. Just as we try to be calm ahead of a tense situation on the road, equally we should take a few breaths before scrolling through timelines.”

The heartstring-tugging adverts might claim that these sites are where true friendships are made, but research** undertaken at the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA) last year found that children’s ability to develop social skills – a crucial part of growing up and forming relationships – is in fact undermined by the use of digital media. Kids in the study who used these sites were less likely to be able to recognise emotions and non-verbal cues in others than those who hadn’t accessed the platforms. According to Dr. Sherry;

“We know that people with a close network of (real) friends live longer, have healthier brains, survive disease better, and get less colds. Clearly, social media isn’t going anywhere but what we need is to make sure we have a minimum, prescribed amount of face-to-face, eye-to-eye, real life contact to avoid detachment, isolation and prevent hurtful online ‘road rage’. This is what in health terms is called a ‘behavioural vaccine’ – the more human contact we have offline, the healthier we can be online.”

This was posted in Bdaily's Members' News section by David Pacini .

Raising the bar to boost North East growth

Raising the bar to boost North East growth

Navigating the messy middle of business growth

Navigating the messy middle of business growth

We must make it easier to hire young people

We must make it easier to hire young people

Why community-based care is key to NHS' future

Why community-based care is key to NHS' future

Culture, confidence and creativity in the North East

Culture, confidence and creativity in the North East

Putting in the groundwork to boost skills

Putting in the groundwork to boost skills

£100,000 milestone drives forward STEM work

£100,000 milestone drives forward STEM work

Restoring confidence for the economic road ahead

Restoring confidence for the economic road ahead

Ready to scale? Buy-and-build offers opportunity

Ready to scale? Buy-and-build offers opportunity

When will our regional economy grow?

When will our regional economy grow?

Creating a thriving North East construction sector

Creating a thriving North East construction sector

Why investors are still backing the North East

Why investors are still backing the North East