New goals – opening up on football and dementia

Dave Watson was one of the toughest footballers to play the game.

And his job, says daughter Gemma, was to head the ball. A lot.

Uncompromising, whole-hearted, no-nonsense.

With the steely stare and thick black sideburns, Dave epitomised the tall centre-back from the 70s and 80s whose primary task – aside from kicking the odd striker – was to head the ball and run through brick walls.

“That was him,” says Gemma, as she reflects on a career which came to an end when she was seven.

“And it’s bittersweet, because he was celebrated for being hard and tough, and headers were what he did best.

“We still celebrate him for that – but at what cost?”

Gemma Jordan, Dave’s youngest daughter, is an award-winning film maker who now lives in the US.

Her previous work includes Netflix production Girls Incarcerated and a series on former Death Row inmate Julius Jones.

Dave and his family – wife Penny and Gemma’s siblings Roger and Heather – went public four years ago after Dave, a member of Sunderland’s FA Cup winning side in 1973 and capped 65 times by England, had been diagnosed with neurodegenerative brain disease a few years earlier.

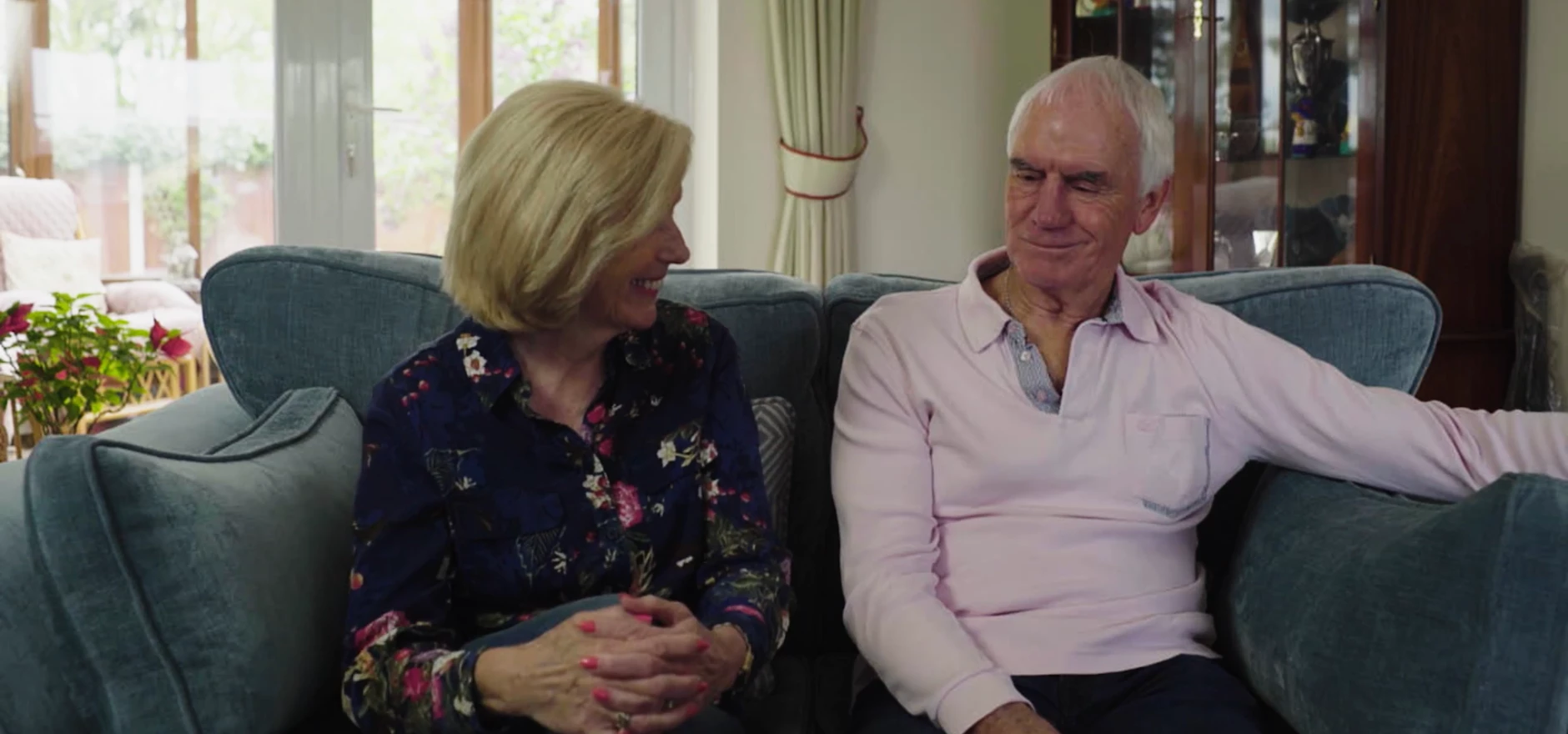

Gemma decided to start making a film about the life of her father – who very recently turned 78 – through fly-on-the-wall moments with Penny and Dave at home, and interviews with former team-mates including Kevin Keegan and Asa Hartford.

And she is now keen to complete filming.

Gemma, who has started a Crowdfunding campaign to raise £27,000, says the cash will help pay for one more fortnight of filming with a British crew and complete her proudest work.

She tells Bdaily: “I always wanted to make a film about him.

“He’s one of those players who didn’t have a huge ego and wasn't the biggest star, but he achieved so much.

“His career, and the way he made it to the top flight, is unusual because he was a bit older.

“Now, of course, the story is different because of the dementia.

“When I first started talking about a documentary, it wasn't out in the open and we decided, as a family, and my dad decided, ‘let's be open about this and get rid of that stigma’, because at that point there was a lot of shame around having dementia.

“He's deteriorating and it's heartbreaking; we know it’s just going to get worse and worse, but he is hanging in there and fighting."

“I’m sure it’s no surprise to people who saw him as a player that he is battling, and I think a lot of it is to do with my mum's involvement.

“She's been quite instrumental in setting up memory clubs at various football clubs and taking him to the different teams he played for who are now doing these memory clubs.

“They are great events and help him have some social interaction.”

When she started filming four years ago, Gemma was interested in football’s inability to deal with the long-term effects of football on brain health.

Several high-profile cases have come to light among ex-footballers since Jeff Astle’s family launched a campaign ten years ago that called for an independent inquiry into the possible links between degenerative brain disease and heading footballs.

Gemma’s mum Penny has been taken on as an independent consultant with the PFA, and has worked alongside Jeff’s daughter Dawn Astle to help set up the union's brain health fund, supported by the Premier League, which aims to assist former players and their families who have been impacted by neurodegenerative diseases.

The Premier League, and similar organisations across the world have brought in guidelines for senior players’ weekly training, and there are worldwide bans on heading for under-age players, but the game – and other sports such as rugby – still has a long way to go to address a difficult issue.

Gemma says: “Part of the reason why I want to make the documentary was to show people what it's like to live with dementia.

“In the beginning, I wanted to investigate, ‘why did this happen to him?’

“There's such a strong link between football and dementia, and there's much higher risk among defenders.

“I was quite angry for a while, and I was trying to figure out who knew about it and brushed it under the rug?

“That was the kind of piece I was heading towards when I saw certain entities were warned about this in the 80s, or even before that, and did nothing.

“But as time has gone on, I've realised I want to celebrate Dad’s life and tell his story.

“I don't want to do a hit piece on football, or on heading.

“It is an issue people need to be talking about and be educated about.

“There is a lot of misinformation out there, so I hope we can clear some of that, but also just raise awareness and let people know it's OK to be open about this.

“There are a lot of ex-players struggling, and what are we going to do to support them and their families?

“Football is football, and it has given our family everything.

“It gave my dad so much joy, and it was his way of providing for his family and making a living.

“We love the game. It's not practical to say, ‘hey, we're gonna ban heading completely’.

“But I do think we need to keep talking about these things and hopefully this documentary is going to open up the conversation, which is quite important, and perhaps be inspiring.”

As for her dad, who also played for Manchester City, Stoke City and Southampton and is now living with wife Penny in Nottingham, he has already said he wouldn’t change his football career.

His 13-year-old grandson Jack is a very good midfielder who ‘loves football’ and plays regularly in the States.

Gemma, who was the outcome of her father’s reverse vasectomy – ‘because he was doing well in the game’ – has had the conversation with him on camera.

She says: “People ask my dad that a lot – ‘with what you know now, would you do anything differently?’

“But I feel it's a bit of an unfair question.

“When you're in your 20s or 30s, trying to provide for your family, you're not really able to think ahead, or how it might affect what you can do with your grandchildren in later life, unless someone puts you in a time machine.

“I definitely know I wouldn’t be here without football.

“So I don't like that question but, at the same time, at the end of the teaser I've made, there is a soundbite from my dad, which I didn't prompt from him, when he was reflecting on himself.

“He came to the conclusion that he doesn't know what's in his head, or what's going on physiologically, but he wouldn't have changed any of it because it’s him and that’s his identity.

“I do think if there was more awareness at the time, he would have considered things differently, and maybe he wouldn't have continued playing as long and retired several years earlier.

“There are guidelines now, and if they had been in place then, I really do think, because he was a professional athlete and very much took care of himself, that if someone had said, ’hey, you know, doing that's gonna give you brain damage in later life?’, he would have adapted.”

Gemma is planning a trip to the UK in early 2025, and hopes to be closer to completing the film then, with additional funding and a UK crew in place.

Her dream is still on course but will depend on the coming weeks, and interest in the project for a real footballing hero of the 70s and 80s whose struggles will resonate with so many.

In the meantime, the whole family will appreciate the precious time with her father.

She adds: “I grew up with people telling me how tough he was, so I always felt like he was completely unbreakable.

“He's just your dad, but when I was 17 or 18, I went to Maine Road to watch Manchester City play, and I didn't know he was going to be there, but he walked out on the pitch before the match and the whole stadium just went crazy.

“I had this amazing experience to see him as such a hero to the fans, and saw him in a different light at that point.

“I’m the youngest.

“He retired when I was about seven, so I was more sheltered from his career.

“But I remember how people would come up in the street and ask for his autograph; I always thought that was funny.

“He was an amazing dad, super engaged with us as children, the dad who would get on the floor and play and mess around with you, just a great sense of humour, very patient and even tempered and chilled – the very opposite of how he played.

“He was so unassuming; I don’t know how he went out and played in front of so many people every week.

“He always encouraged me to follow my dreams and see things through.

“That’s why I am determined to finish this documentary.”

To support Gemma’s funding campaign, click here

Want your business, product or service to be seen regionally and nationally? Bdaily helps you get your story in front of the right audience, every day. Find out how Bdaily can help →

Join more than 55,000 subscribers by signing up to our daily bulletin each morning here.

Don't get caught out by employment law change

Don't get caught out by employment law change

When literacy thrives, our businesses thrive too

When literacy thrives, our businesses thrive too

Building a more diverse construction sector

Building a more diverse construction sector

The value of using data like a Premier League club

The value of using data like a Premier League club

Raising the bar to boost North East growth

Raising the bar to boost North East growth

Navigating the messy middle of business growth

Navigating the messy middle of business growth

We must make it easier to hire young people

We must make it easier to hire young people

Why community-based care is key to NHS' future

Why community-based care is key to NHS' future

Culture, confidence and creativity in the North East

Culture, confidence and creativity in the North East

Putting in the groundwork to boost skills

Putting in the groundwork to boost skills

£100,000 milestone drives forward STEM work

£100,000 milestone drives forward STEM work

Restoring confidence for the economic road ahead

Restoring confidence for the economic road ahead